By Andrew Danielson / Photos by Lauren Lee and Justin Moore

A species of ground squirrels. A unique camera trap with motion-activated cameras. And the states of California and Rhode Island.

As it turns out, all those items have a lot in common, particularly when it comes to the wildlife biology laboratory of Dr. Scott Bergeson, associate professor of animal biology at Purdue University Fort Wayne in the department of biological sciences.

For over a year, two of Bergeson’s graduate students, Justin Moore, originally from Rhode Island, and Lauren Lee, who hails from California, have been working on separate but complementary research projects focusing on wildlife conservation and management.

Lee, who received her undergraduate degree in biology from the University of California, Santa Barbara, is working on a project to survey and identify the variety of small mammal species that exist throughout Indiana.

“The goal is to survey the entire state for small mammals,” Lee said.

Lee’s mentor, Bergeson, explained that the last time a survey of small mammals in Indiana was completed was around 2007. That means that wildlife conservation officials such as those at the Indiana Department of Natural Resources have no fresh statistics on the health and population figures for small mammals.

Mammals are good indicators of the health of a particular ecosystem. If there is a diverse population of mammals in the area, that ecosystem is probably healthy.

“All of these small mammals and all of the other things help maintain the health of these natural spaces,” Bergeson said. “Even our agriculture would suffer if we didn’t have the natural spaces that help filter the pollutants that would otherwise get into our crops. Everything is connected.”

Smile – You’re on Camera

Lee’s project, which is funded by a $150k grant from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, is ambitious to say the least. If she were to use traditional trapping methods to conduct her survey, as was done in the 1960s, her project would take many years to complete.

But Lee and Bergeson have a solution: camera technology and upside-down buckets.

Lee explained that she installs “camera traps” on publicly-owned property, at least 100 meters away from any trail or road.

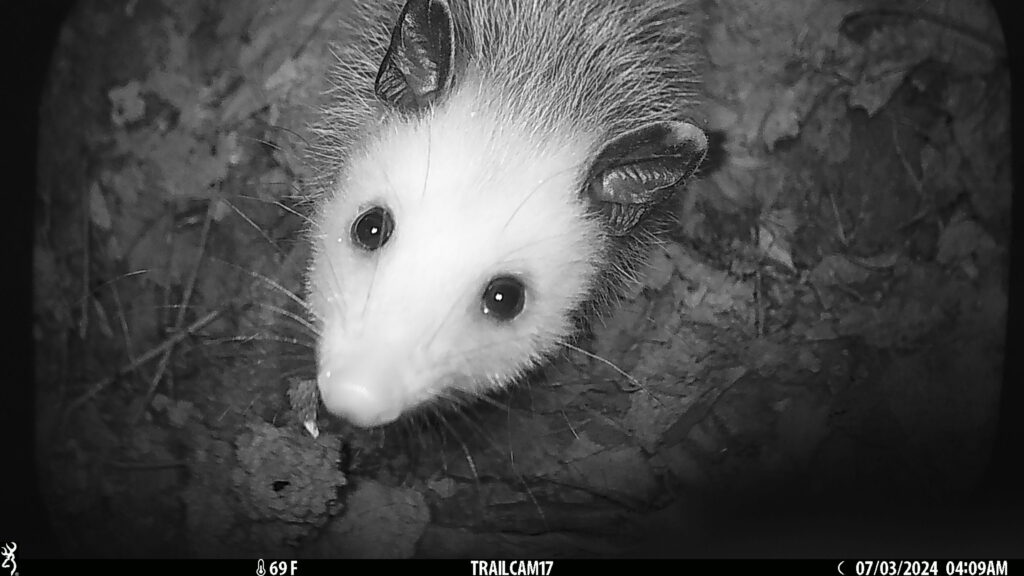

Each camera trap consists of a temporary “wall” made of a plastic material that leads to overturned buckets. An upside-down bucket with entrance holes cut into the bottom houses the actual camera.

The traps don’t use any bait, relying instead on animals’ natural curiosity or scent. When an animal approaches the trap, the “wall” barrier naturally guides them to the hole in the bucket. Once the animal walks into the bucket, their photo is snapped.

The cameras are infrared-equipped and motion activated, so there’s no bright flashes when the camera snaps photos. The lenses used on the camera are designed to provide close-up, magnified views of the animals, providing easier identification of the small furry visitors.

Lee explained that she currently has 102 camera trap sites, spread across the entire state. To collect the photos taken from her cameras, she has to drive to each site, swap out SD cards in the cameras, and perform maintenance on the site as needed.

From those sites, Lee has collected 1.5 million photos, with hundreds of thousands of photo sequences.

To help collect and process all of that information, Lee is being assisted by two undergraduate technicians and an artificial intelligence software. The AI automatically sorts through the sequences of photos and provides Lee with some basic species identification. She then checks what the artificial intelligence has done, making sure that the identifications are accurate.

“So, the whole idea is that we have this huge database of photos from everywhere and then for the next 100 years we can start mining that data to figure out other sorts of things,” Bergeson said.

A Squirrel’s View on Indiana

Yet another of Bergeson’s graduate students, Justin Moore, is also undertaking an ambitious wildlife conservation project with the assistance of two undergraduate technicians.

Moore, who received his undergraduate degree in wildlife conservation from the University of Rhode Island, is working to help stabilize a population of ground squirrels here in Indiana, called the Franklin’s ground squirrel.

Moore explained that ground squirrels are similar to tree squirrels, but they’re actually separate species with different diets, preferred habitat, and behavior.

According to Moore, Franklin’s used to have a fairly wide range in Indiana. However, due to the loss of prairies across the state, the ground squirrel’s preferred habitat, that population has shrunk to just one natural population in the region.

“They are state endangered in Indiana, and they’re declining across most of the Midwest,” Moore said.

Moore’e project, which is also fully funded by a roughly $200k grant from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, is to help stabilize the Franklin’s population by re-locating healthy specimens from other states to Indiana. His project is a pilot study, so the techniques he is using will help in future re-location projects of either Franklin’s or other small animals that are endangered.

How to Move a Squirrel: Carefully!

Moore explained that, together with his mentor Bergeson, they identified a strong, healthy population of Franklin’s in South Dakota. Moore and Bergeson quickly formed an agreement between wildlife conservation officials in South Dakota and Indiana, enabling them to bring Franklin’s from South Dakota back here to Indiana.

But moving squirrels is no easy task.

“There’s a lot that goes into the trapping to make sure that the squirrels and we [the researchers] are safe,” Moore said.

The capture sites for the squirrels in South Dakota are designed to minimize stress and discomfort to the animals, including routine checks on the traps and special coverings to provide shade to captured animals in the traps.

Researchers receive rabies vaccines before interacting with the animals, and all captured animals are initially handled through special handling cones that keep the squirrels calm and unable to bite the researchers.

Once the animals have been captured, they undergo a thorough process of medical checkups, including treatments for any diseases spread by ticks or lice. A veterinarian check-up and a full 21-day quarantine period are also rigorously followed to ensure that diseased animals are not brought into Indiana.

Once Moore brings the squirrels to Indiana, he releases them into what are called “soft release” enclosures, allowing the newly translocated squirrels to get used to their new habitat before being fully released into their Indiana home.

To keep tabs on the squirrel population and its well-being, Moore uses small radio transmitters attached to the Franklin’s that allow him to track their movements using a small receiver and antenna.

The new Franklin’s ground squirrels being brought to Indiana are being released in Newton County on property owned by The Nature Conservancy, a non-profit group that advocates for wildlife conservation.

PFW Biology Students Having National Impact with Research

Both of these research projects are forging new ground in the world of wildlife conservation.

Dr. Bergeson said that Lee’s project has already resulted in a research protocol that is now being shared among various states engaged in wildlife research. That protocol, coupled together with her unique use of artificial intelligence, will provide other researchers with tools and techniques needed in today’s field of wildlife conservation.

Moore’s project is also making inroads into the field of wildlife conservation.

As he talked about his project, Moore said that the project will hopefully result in Franklin’s populations stabilizing. That means the population will, one day, grow strong enough to be removed from the state endangered classification.

And these projects are already paying dividends for their researchers, as Moore, Lee, and their technicians, all gain conservation experience from their projects.

“I feel like any new experience with any kind of wildlife is really, really cool,” Lee said.

Moore agrees with that view.

“I couldn’t imagine doing anything else,” he summarized.

It’s a win-win situation for Lee, Moore, and their two undergraduate research technicians who assist them with their projects. They all gain valuable research experience and the opportunities to do future projects or write and publish their findings in research journals.

For the undergraduate technicians, the field research training they are gaining will help them strengthen their potential future applications to graduate school.

But perhaps the greatest benefit these projects are providing is the effect they have on wildlife conservation.

Bergeson said that projects like Lee’s camera traps and Moore’s squirrel translocations are having valuable impacts on Indiana’s conservation efforts.

“Our lab has actual impacts on that, which is super cool,” Bergeson said.