Climate change is often discussed as a steady rise in global temperatures, tenths of a degree here, incremental carbon emissions there. But the more urgent concern among scientists is not just gradual warming. It is the risk of crossing crucial tipping points: critical thresholds in Earth’s climate system where small increases in temperature can trigger abrupt, self-reinforcing, and potentially irreversible change.

A tipping point occurs when a climate system shifts from a stable existence into rapid transformation. Once crossed, feedback loops amplify the damage, making it difficult—or in some cases impossible—to reverse, even if temperatures later stabilize.

These tipping elements exist across the planet: in ice sheets, forests, permafrost, coral reefs, and ocean circulation systems. Scientists warn that several of them are already under stress as global temperatures rise more than 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels. Crossing 1.5°C to 2°C could push multiple systems beyond their limits.

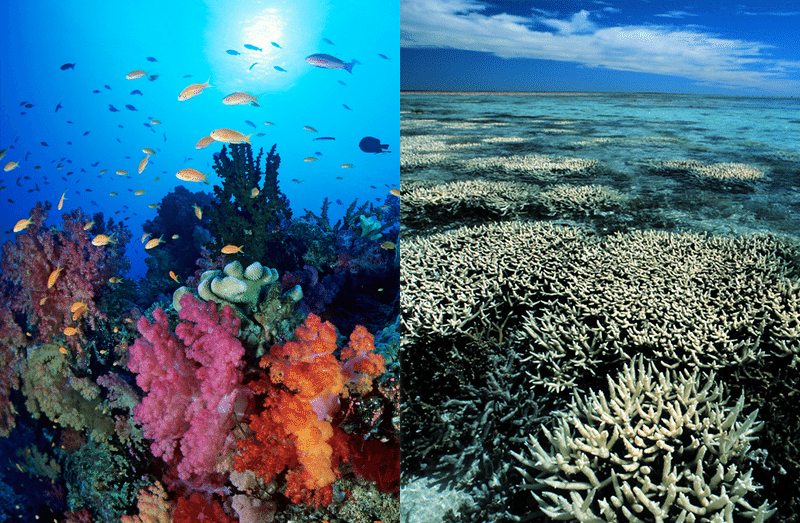

One of the clearest and most immediate examples is coral reef collapse.

Left photo by Gary Bell / Oceanwideimages.com. Right photo by Greenpeace / Roger Grace.

Coral reefs are extraordinarily sensitive to temperature. A sustained increase of just 1–2°C can trigger coral bleaching, a process in which corals expel the symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) that provide them with food and color. Without these algae, corals lose both their vibrant appearance and their primary energy source.

The world has already experienced multiple global bleaching events, including severe episodes in 1998, 2010, and 2016–2017. In 2016 alone, approximately 29% of coral in the northern section of the Great Barrier Reef died in a single year due to extreme marine heat.

Bleaching becomes a tipping point when it happens too frequently. If reefs do not have time to recover between heat events, they shift from vibrant, biodiverse ecosystems into algae-dominated rubble. Once that shift occurs, erosion accelerates, fish populations decline, and water quality worsens. Even if ocean temperatures later stabilize, the ecological structure needed for recovery may be gone.

This matters far beyond marine biology. Coral reefs support roughly a quarter of all ocean species and provide food security, tourism revenue, and coastal protection for more than 500 million people worldwide. Their collapse would represent not just an ecological tipping point, but a social and economic one.

Coral reefs are not alone in facing dangerous thresholds.

The Amazon Rainforest presents another looming tipping element. Often called the “lungs of the Earth,” the Amazon plays a crucial role in carbon storage and rainfall regulation. But deforestation, drought, and climate change are pushing it toward a savanna-like state.

Roughly 17% of the forest has already been lost. Scientists estimate that crossing a 20–25% deforestation threshold could trigger widespread dieback, as the rainforest would no longer generate enough moisture to sustain itself. Such a shift would release vast amounts of stored carbon, intensify regional drought, and disrupt global climate systems.

Communities living in the Amazon are already experiencing longer dry seasons and more frequent wildfires. The tipping point is not theoretical—it is unfolding in real time.

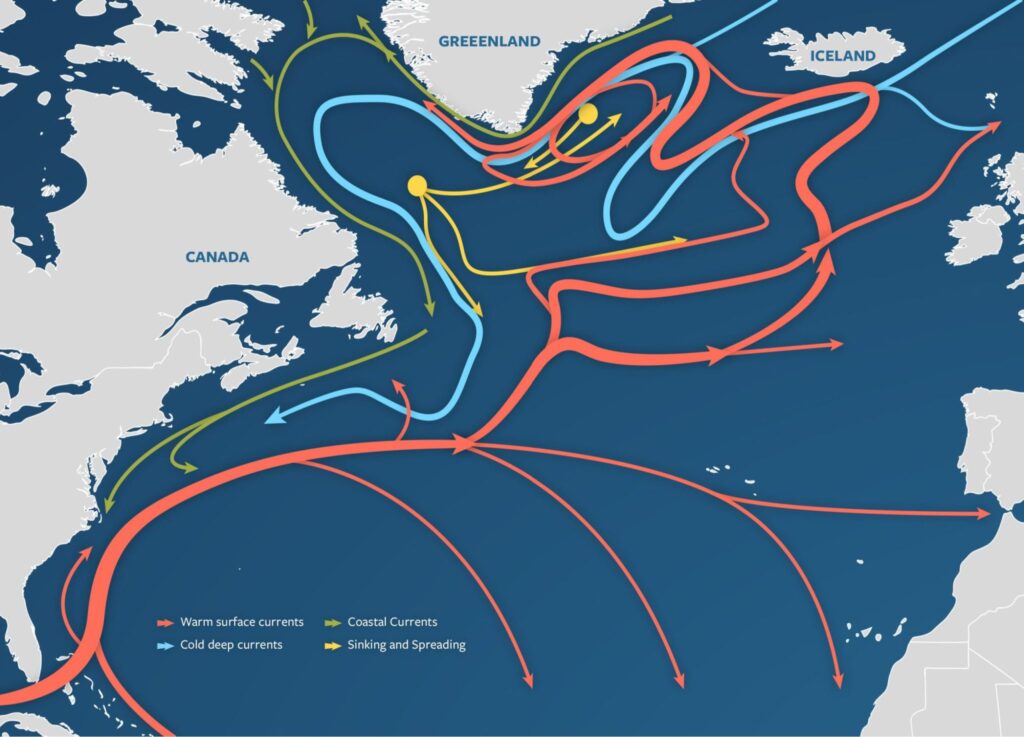

The Atlantic Ocean contains yet another tipping element: the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This vast system of currents acts like a global conveyor belt, moving warm water northward and cold water southward. It plays a critical role in regulating the climate, particularly in Europe.

Freshwater from melting Greenland ice disrupts the salinity balance that drives this circulation. Evidence suggests the AMOC has weakened by roughly 15% over the past half-century. Continued slowdown could dramatically alter weather patterns, disrupt food systems, and intensify regional climate extremes.

Each of these tipping points is different. But they share a common feature: once these negative feedback loops take hold, change accelerates.

Yet these systems are not beyond influence. The difference between 1.5°C and 2°C of warming may determine whether coral reefs survive in reduced form or largely vanish. It may shape whether ice sheet melt accelerates gradually or crosses into a runaway decline.

Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions remains the most critical action. Limiting warming slows feedback loops before they spin out of control. This, of course, faces limitations as our government has recently limited its ability to regulate emissions.

Local and regional measures matter as well. Marine Protected Areas can strengthen coral resilience by reducing overfishing and pollution. Coral restoration efforts—nurseries, selective breeding for heat tolerance, assisted gene flow—are being tested. Improving water quality reduces stress on reef systems. Early warning systems allow faster response to marine heatwaves.

The concept of tipping points can feel overwhelming. The language of it all: irreversible, collapse, runaway, all suggest inevitability.

But tipping points are thresholds, not set-in-stone prophecies.

The climate system responds to actions, not despair. Slowing warming slows negative climate feedback. Stabilizing temperatures stabilizes systems. Action taken before thresholds are crossed carries far greater impact than action delayed.

The lesson of climate tipping points is not that collapse is certain. It is that timing matters. The window for avoiding the most destabilizing shifts is narrower than it once was, but it remains open for now.

Whether these systems cross their thresholds depends on decisions made in the present, not centuries from now.